-

I am not okay with spewing things into the air that may change the colour of the sky to white just because the species I am part of has already spewed so much crap into the atmosphere that the climates we’ve taken for granted as life-supporting are changing in ways that will make fewer locations capable of hosting our ungrateful asses. I am especially against this decision ever being made to attempt this techie “fix” because it wouldn’t actually “fix” anything, only possibly buy a little more time for some while possibly exacerbating problems for many others. Those “others” most likely being those who have already suffered most in the Anthropocene – our non-human relatives and the homo sapiens who saw most or all of their former ways of life beaten out by the various imperialistic/colonizing forces of Europe, the USA, and all the predations of economic systems that reward only the most ruthless in any group of humans.

The author is best known for her earlier book, The Sixth Extinction, a book I’m loath to read as the only thing that truly makes me sad when considering planetary destruction is our ongoing murder of all of our non-human, non-domesticated relatives. Their extinctions happen mostly because the real effort required to protect them would mess with our money. Money is what we’ve been made to rely on more than clean air & water because the inability to access whatever monetary units change hands in whichever nation we reside will render a person unable to access anything except outdoor air, which is usually polluted anyway.

But there are still (too) many who want to think that we can science our way out of this mess we’ve made. That we can create artificial carbon capture methods that will somehow work better than the billions of trees we’ve consumed in order to make the land more amendable to agriculture, to get the lumber needed to build more structures for more humans who can afford the costs to live in them, to pulp the paper so we could publish the good news of our domination over Nature and still have enough to flush away in our water wasting toilets. Why, yes, I am a little bitter – what makes you ask?

As a kid, I remember reading about examples of humans overcoming a Natural barrier to what they wanted (cheap food, easily navigated rivers, more power – electrical & otherwise) and subsequently creating another problem via their disruption of the existing ecosystems. They would then try to “fix” the man made problem, not by stopping or undoing what they’d done and accepting that what they wanted was not what they should have, but by introducing a new layer of problem into the mix. Examples would be cane toads, the Dust Bowl, Galveston’s sand bar … At some point, one would think that we would realize that constant growth, constant expansion, constant consuming is not something we can continue to indulge in and instead start figuring out ways to slow down & redirect our efforts into making sure that everyone has enough while learning that having more of everything is no longer a given.

But, no. The people and places the author visits are just more of the same – people trying to figure out how to use science and tech to keep Nature from killing us without our having to actually change anything about the way we’ve been doing things. My absolute favourite book this year has a word for those of us currently avoiding doing the things that would actually address the actual problem (dismantling financial systems, stopping all non-essential “work”, allowing exploited peoples to decolonize & develop & teach the ways of living with their lands that aren’t based in constant extraction, oh and learning how to limit human population in order that non-human kin can have a chance to heal). That word is “fuckwits”.

Because Ms Kolbert finds no real hope in the places she visits for this book, many will bypass it, much as they might bypass last year’s Farewell to Ice or the latest news reports on ocean temperatures, glacial melt, or microplastics being found in all of the planet’s surface water, including rain. Ms Kolbert delivers the bad news so gently, however, it really doesn’t hurt, especially if it’s not news but just more examples of how, although humans are busy doing something, they’re mostly not doing anything helpful.

-

Every now and then, someone puts music and lit together in a way that just … bangs! It was so hard to not believe that this wasn’t a true story, that back in the day an amazing Black woman rocker hadn’t had her career sidelined by a wyte man and the industry and culture that fawns over those like him while pretending people like her just don’t matter as much since they simply aren’t as marketable and/or using them as – well, just using them in any way they see fit if they see it’ll give them a boost …

But it is a fiction, though the characters certainly took the forms of real-life famous & infamous people who’ve graced the pages of The Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, etc. in my head as I devoured this book. I listened to the author give a couple of interviews and her concept was so spot-on that I couldn’t wait to lose myself in her work. She spoke of Nona Hendryx & Betty Davis & Grace Jones and punk and these are all a few of my favourite things so the anticipation to see what kind of person she would create with this premise was beyond high.

Ms Walton tells the story through the work of another writer, Sunny, a journalist who has landed a rare spot on a music magazine’s masthead AND whose father was the drummer for Opal & Nev (he was killed at a riot when the band’s label put them on a bill with some southern rockers of the sort who wave the Stars&Bars as a call out to their fans of choice). This allows the book to use the framework of being an oral history about the duo (but mostly about Opal) with statements from multiple interviews making up a lot of the text. Sunny’s personal tie to Opal is based in tragedy and slowly the real story of what actually happened before an iconic photograph was taken gets uncovered, I don’t know who all will be surprised but it certainly rings true. Sunny is able to write in depth about this woman because a revival concert has been planned so Opal & Nev are once again in the news but we are constantly reminded that normally Opal would not be given so much space to fill.

None of the characters are all that likable, but artists and creative types are not always known for their winning personalities. This made it more realistic, as did the use of so many different voices talking about Opal’s life and their relationship with her and/or her work: family, friends, business people, and even some non-fictional artists. The most positive words tend to come from those with the least face-to-face time with the subject, but even those who don’t have too much good to say generally know that Opal is not someone to dismiss easily. And this book is not one to be put down easily either.

-

I consider Super Sad True Love Story to be right up there with Oryx & Crake as perfect speculative fiction as it also seem to take what we have now, society-wise, and project that into a tale of a perfectly dystopian near-future of capitalism run amok where ThePowersThatBeTM are at least a bit more honest about Life being far less important than Finance.

This novel is set in the mostly-real world of first wave Covid-19, where people who could were happy to leave their lives in the metropolis and try to hide out in the countryside, alongside the people who, among other things, probably didn’t vote like them in the last election. Although Shteyngart has been focused on the world of the “Haves” in this and his last novel, Lake Success, most of the “Haves” in this tale are a lot less secure in their bank accounts and their debts weigh far heavier on them than on Lake‘s protagonist. They are also mostly immigrants or first generation US citizens, so there’s also that.

Masha and Sasha, the hosts, are not playing from the same script: Sasha envisions a summer camp for adults reminiscent of the vacation colony of Russian Jews he remembers from their youth. Masha is more bound up in trying to protect their adopted daughter, of Asian descent, from Covid and the world’s harshness in general. Nat, the daughter, would like to figure out who she is – as an adopted child being raised by people deeply embedded in a birth culture not much like that of her biological parents, this makes sense. Their friends and other guests are a mixed bag: Karen Cho, who made a fortune off a social app, and Vinod Mehta, who has little in his bank account, are old friends from college; Karen’s cousin, Ed, is well-heeled & sophisticatedly urbane. And then there are the outliers: Dee, Sasha’s former student, and The Actor, a celebrity who Sasha needs to work with in order to get the cash flow necessary for maintaining the country estate they’re on.

I hope you like Chekov (the writer, not the Star Trek character) because an appreciation of the Good Doctor’s work will allow you to soak up so many beautiful more layers of humour and tragedy from the goings-on in this place removed from the city. Not gonna lie, one chapter had me in tears as Shteyngart inserts Uncle Vanya (my fave) directly into the tale for perfect effect.

Luckily, Chekov is not a prerequisite for enjoying this novel: a willingness to let yourself soak in the lives of people who are probably nothing like you via paragraphs that expose the inner and outer workings of these friends & acquaintances who are riding out a storm on an increasingly rickety raft that is hard to stay on while also maintaining some sense of social distancing. Throw in some social media/tech-induced drama and … well, this isn’t a story for those who must have happy endings, ok?

-

You wanna see a great movie? Watch Sorry to Bother You, Boots Riley’s anti-capitalist, pro-union, fantastical sci-fi set perfectly in the current hellscape we call the good ol’ USofA. The soundtrack alone is pure fire.

Black Buck is less fantastical, more reality-bound satire, but also centers on the problems of trying to achieve “success” within a system that was never really designed to offer anything of non-monetary substance to anyone and especially not to anyone with skintones darker than a paper bag. It even centers on sales as the talent to be exploited. Sadly, unlike Sorry, the end of this tale doesn’t encourage getting rid of a failed system but is instead a rallying cry for POC to embed ourselves into the corporate entities that are busy destroying things faster and faster in pursuit of those benjamins so we can collect a few on our way to global collapse.

But it’s a good story, damnit. I found myself riding along with Buck as he descended deeper & deeper into being his absolute worst (and therefore his company’s best performer) and enjoying the side characters (at least those that weren’t absolutely vile, but really not unbelievable racists) as they whirled along with a plot that was wildly all over the place at times, but still – to me anyway – pretty captivating in that it kept me going with a “now what’s going to happen?” attitude. Sure I wanted more politically out of this, but, alas, that was not to be. I just had to enjoy it for what is was – a rollicking yarn.

Sometimes a story is just a story and that is just fine. Entertain me.

-

Southern women and charming vampires is familiar territory. I miss Sookie Stackhouse and the completely separate (and more diverse) ‘verse of True Blood, tho’ to be honest I never finished the tv series due to a dislike of Sookie’s escape into faerie land ending the last season I watched. Aaaanyway, I grabbed this little gem off public library shelves because I love Bahni Turpin’s voice and I believe the back cover mentioned “humour”.

I browsed through the comments on Good Reads and found the most-liked review was by a white guy who had just also read Hood Feminism (one of my fave books of 2020) who felt that the book (written by another white guy) did nothing right by its Black or female characters, stating that he noticed in the first half of the book that, “the Black characters in the book were only ever unnamed waiters or caregivers without speaking roles and it felt iffy.” Considering that the story is set during the ’80s-’90s in a middle class white suburb of Charleston, I was actually sort of surprised when there were suddenly Black characters along with a back story of racist violence that was not out of character for the US South. Yes, the Black characters in this novel live in a far less affluent neighbourhood that most of the nice white ladies are terrified to venture into, as they have been carefully taught to imagine the worst. But those Black people have plenty to say and we hear their names loud and clear, if mostly through the character of Mrs. Greene, the character who bridges the two communities. And when the young Black men do act threateningly to uninvited white visitors, we quickly learn it is because they are acting from a state of heightened defense as it is evident that their community is again under a direct attack by unidentified white people.

All of the characters in this story are people who have been born into a world of very clear boundaries and beliefs that keep Black and non-Black people living away from each other, men and women running in different spheres of influence, women competing for what little power is allowed them, and this is all very clearly in service of – tinhorn fanfare, please – the straight white men who rule over all. As nice married ladies, the white women who are the main characters, have signed over pretty much all sense of agency to their petty, greedy, and small-minded husbands. Any moves that are made without the blessing of the men who band together easily to protect their power are quickly squashed and justified as being in the best interest of the women they claim to protect, rather than just control. Most of the women give little thought to their golden cages until they realize their children, and not just the children of the Black community, are apt to be sacrificed to the vampiric stranger who has embedded himself as the benefactor of their little society, running financial schemes that enrich the white men and inflate their already unjustifiably inflated egos. The husbands’ wonderfully white supremacist way of ignoring any history or facts or evidence that would contradict their right to do as they please to make more money and run things to suit only themselves – and their wives’ willingness to swallow it all to keep themselves only one rung below the men, but above so many others – is a perfect mirror of what can be seen in real life.

No one person can fix the horrific mess that these people unleashed upon themselves and I would say that it is in making the project a group project to save themselves that the Good Read’s reviewer’s “White Saviour” claim non-applicable to this story. Every woman has a part to play, everyone gets dirty, and the benefits are only Big Picture: not so great on the small scale.

This tale takes place before smart phones and other tech that might have helped the women suss out the real dangers (as opposed to the financial & social currency threats that keep them toeing the party line through too much of the book) and put together a plan with a bit more ease. There was also enough humour to keep me going – Grace, the main character, has her moments due to her growing inability to function within the constraints of her indoctrination which she realizes are completely divorced from the reality and/or humanity, which makes sense given the relation of oppression to humour. Some things only hit you later, as when you remember that the book Grace failed to read for her original book club was Cry the Beloved Country – would the book have given her a little more understanding of systemic inequality had she read and discussed it before all hell broke loose?

The detailed ick factor is super high and there’s even a very unsettling rape, so be warned. I only wish that ALL the monsters in this tale got a taste of real and gory justice.

-

When people start banging on about how overpopulation is not a problem because there are more than enough room/resources to maintain every single human and the only problem is that elites are hoarding everything, it’s all I can do not to scream because, while yes, the ownership class has privatized the shit out of potable water and arable land, everyday humans are also spoiling a vast amount of life-supporting water, land, and air trying to maintain the style many have become accustomed to living in (or by just trying to survive in some instances) – and a lot of that pollution comes from dealing with the waste we produce as consumers & some from just being bioforms with a physical need to excrete. There’s also the problem of what to do with the husks we leave once the Spark of Life has left the building:

I personally find cemeteries much more attractive than golf courses, but both take a lot of space that may be better used for the Living. In this book, the founder of The Order of The Good Death travels the world for us and finds how different groups/communities deal with death and body disposal in ways that do and don’t allow for Death & the Dead to be acknowledged and embraced by the living who remain. Not that the cultures that encourage the dead to remain in the home for as long as is possible are super appetizing to moi, but such traditions work for those people and allow much of the deceased, physically & otherwise, to remain included and integrated in their societies.

A lot of what the author and The Order of The Good Death (please check out their website) are working on here is just getting westerners back into the death process. Having relatively recently seen my father take his last breath, ducked out so my niece (she works hospice) and her boss could tidy him up and then said goodbye to his physical form on the front sidewalk as the mortuary wheeled him off to be returned eventually in ash form, the whole concept of how removed most of us have gotten from death work hit home. I don’t know if I would have been down with washing the body, but the author states that death care could be as simple as combing the corpse’s hair one last time. Baby steps, as needed.

I’m pro-cremation, myself (and who knew there’s a community in Colorado who does it out in the open?), but there is a serious issue of the resources required to reduce our juicy selves down to ash. Adding to the problem, living in a society that is really just an economic system means finances are directly tied to how one sees their loved ones off and the inequities are many. This book offers much to think about and will hopefully open minds to considering ways of dealing with Death and the Dead that will enrich rather than deplete our Lives and our World.

-

As someone who only half-watched The Other Boleyn Girl, I truly had no idea that the author had something like this little trilogy (Wildacre, The Favoured Child, & Meridon) under her belt. In looking over some of the everyday reader reviews, I saw they all focused negatively on the sex in the book and “unlikeability” of the main characters. Apparently I’m one of some microscopic minority who read this as a story about land and how complete privatization (enclosure of the commons) destroys entire communities that were previously able to move somewhat past the injustices of the past to a point where slightly smaller but less bloody, injustices could be endured with the understanding that those with damn little would at least have enough sustenance & shelter & self sufficiency to make it worth getting up in the morning to work to provide their “betters” with an even better level of comfort.

When the gentry break the standing social contract with the village and begin claiming sole rights to the use of ALL the land in order to make more cash (because everyone’s doing it, hey – capital is king and land is just that: a financial asset to be squeezed for every ounce of profit … not the living breathing entity that the first of the 3 women in these 3 books knows in her blood as a sibling when the tale begins) all hell breaks loose and everyone will suffer. Sure there’s incest, but haven’t those in power always indulged in breeding with direct family members in order to keep the ownership of all they claim close and completely within their own ranks, hemophilia & oversized jaws be damned?

The lengths to which the first woman goes to try and “own” her land only serve to separate her from what she wants – one could blame patriarchy for poisoning her mind with the whole concept of “ownership” while simultaneously denying her that privilege because of her lack of penis. Her offspring spends the next book trying to overcome the well-meant attempts of her guardians to water down the spirit she should have inherited from her dam in the interest of making her a better person – while unfortunately not drowning her cousin/brother who freely develops all the bad habits that he feels he has the right to as a person of penis. The last spawn is sent away from the land and lives a live of non-luxury but loves her faux sister with the desperation her grandmother had for the fields & forests – so we know she is capable of feeling for something other than herself. Although sorely tempted to become as selfish as anyone else in her birth class once restored to her “rightful” place, she also has some guidance from an elder who already paid a huge price for hubris and greed (kept his dick but lost a couple of other appendages). Obviously, any sense of balance is probably extremely temporary in a world where inequity is normalized and any concept of society is really just a ruse for maintaining an economic system that relies on haves and have-nots. Still, the ending does offer a bit of respite.

So, thank you, Ms, Gregory, for putting your anti-Tory beliefs down on paper in a series that doesn’t require it’s female protagonists to be likeable – just attractive & ultimately strong enough to do what needs to be done in order to get to the next generation (or to receive comeuppance for an unforgivable fuckup).

-

This was one of those books about people living such a different experience from mine that had me constantly stopping to smh & wonder, “How do they keep going on like that?” Obviously, addiction is a hurdle that a person with damn little self-esteem or sense of worth is going to have a hell of a time trying to get over. And draggging new humans into the world with no real sense or ability to care for and bring them up properly isn’t going to make any of this any easier. For anyone.

I worried that this was some sort of poverty porn, some sort of “well at least I’m not THAT fucked up/fucked over,” pat on the back: but it doesn’t leave me with a sense of superiority, but with a desire to learn more about how one gets into such a bad situation. These depths of sadness and despair can’t be laid only at the feet of the individuals who spend their energies trying to game a system that seems content to blame them for every failing while offering little or no respite from the grinding work of being poor & pathetic. Because it does take a lot of work not to wind up even farther down the social ladder than where Shuggie & his mum reside. I mean, they’re downwardly mobile, but they are trying to slow that descent as much as is possible given their limited resources.

It’s not an uplifting tale of resilience but an captivatingly written series of snapshots of a mother with 3 children trying to live in and about 1980’s Glasgow at the mercy of misogyny, homophobia, alcoholism, capitalism, and the shattered dreams and subsequent apathy that flourish in those conditions. I mean, not everybody dies, but the future for the survivors doesn’t seem to require any sort of eye protection, well, except maybe to keep the shards of metal & glass out.

-

I do love short stories. Bonbons in the world of fiction, they can be consumed in one or two bites and the best are filled with a powerful flavour that can make one long for more or be intensely satiated for much longer than it took to read them. Neither Asian-themed bonbons or full-course meals have appeared on my mela plan for a while, so after hearing a snippet of “Lulu” on, I think, The New Yorker Radio Hour, I felt I needed to hear the rest of the story.

These stories, quite wonderful in their scope, are set in a modern China and are about the people who live as individuals and in communities in a country that decided to try something completely different decades ago. A country that still suffers from some of the same problems haunting the countries that applied even fewer tweaks to the top-down systems that have run the world since humans started hoarding necessities (and continue to run it down as I type). Te-Ping Chen is a journalist at the Wall Street Journal and her writing style is probably all the easier to follow because of it. Her politics are also pretty much in keeping with what one would expect from a WSJ employee, but not overly so – she gets that having one’s material needs met in a country that has collective memories of war & famine horrors happening over & over regardless of who was in-charge can be a major behaviour motivator.

And these stories definitely explore the whys of people doing things: things that are or are not in their best immediate or long-term interests; things that are pleasurable or possibly self-harming; things that are done by choice or possibly by a mere desire to not rock the boat. Motivations are not so much spelled out (thank you!) but we, as readers, are given lots of information and should be able to figure out what’s going on in the heads of these characters … and wonder if we would do the same. Would we indulge in the new fruit? Would we stay in the train station? Would we blame the government for everything?

-

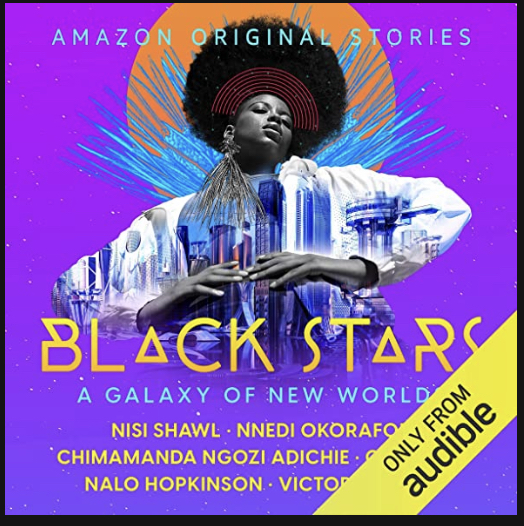

To be perfectly honest, it was Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s name that made me pick up this collection: sci-fi is not my fave genre but N.K. Jemisin didn’t release another bunch of shorts and these were stories that promised a variety of styles (hard and soft) so I knew I’d simply have to enjoy at least 3 of them. False: I liked them all. Of course Adichie’s “The Visit” was my fave (and more like an alternate reality than pure sci-fi, along the lines of Lesley Nneka Arimah’s “Skinned”), but even the stories that were tech or space heavy were easy enough to lose myself in.

I think that maybe I find a lot of conventional sci-fi hard to embrace because a lot of it just ignores or breezes over the bleak history of humanity that got the characters to their brave new worlds (Firefly hooked me because its world is one where English at least lost out as the dominant language). In these stories, the main characters are all too cognizant of the lives their ancestors lived, not to mention that there are sometimes still others living nearby who have no intention of allowing people whose melanin is relevant to ever live in peace.

These stories offer a lot to think about, like a Butler or Le Guin story. At least three made me want a novel so the concepts could be explored at length. But all worked perfectly as short stories.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.